What Does It Mean to Be Appalachian?

Like everyone else, I can choose any number of words to describe myself: educator, wife, author, mother, Christian, beekeeper. These are all accurate, and while I can certainly elaborate on each one, they are concepts that are generally familiar to most people. Some of them invite debate, of course, and certainly they may not be defined in exactly the same way by everyone. One term that I use to identify myself may be even more complex and debated, perhaps because there is so much confusion about what it means or even the place to which it is connected.

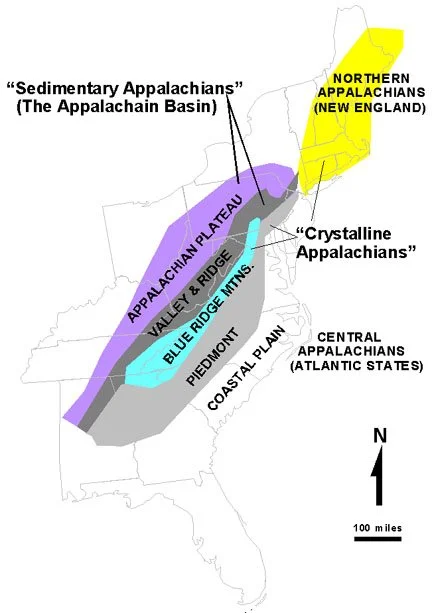

Appalachia, as a place, does not have a strict location on the map. While towns and counties here often have signs welcoming visitors and carefully drawn borders and city limits visible on maps, “Appalachia” has a number of possible definitions. Geographers, geologists, ecologists, sociologists, economists, and the people who actually live here may draw various maps of the Appalachian region. The one approved by the US Geological Survey is my favorite, accurately depicting the most accepted definition of the region as well as its subregions, specifically the Cumberland Plateau, the Ridge and Valley, the Blue Ridge, and the Piedmont. For the past few decades, I have lived in the Blue Ridge region, the region generally most praised for its beauty, in part, due to the fact that it does not contain coal seams and has thus been blessedly free of the coal-mining operations that have damaged the people and terrain of the Cumberland Plateau and Ridge and Valley regions. I grew up in the Cumberland Plateau, and my people primarily hail from there and the Ridge and Valley regions. The Appalachian mountains themselves are remarkable, running up the eastern edge of North America and falling off into the ocean. On the other side of the world, the mountains re-emerge in Scotland. The mineral that runs through the mountains, serpentine, forms a connection that bestselling author Sharyn McCrumb beautifully describes as “serpentine chain,” binding the New World to the Old in geology and culture.

Appalachian culture is a vertical culture, connecting people and practice regardless of state lines. Here in western North Carolina, we have much more in common with people in eastern Kentucky or southeastern Virginia than we do with those in Wilmington. When I speak of an aspect of Appalachian culture, I may be referring to something from my childhood in Kentucky, from my volunteer work in eastern Tennessee, or from my daily life in western North Carolina, as these are all part of the same culture.

Really, though, it is not surprising that there is confusion about the location of Appalachia. The mountains were named after the Apalachee tribe of native Americans, who never lived here and were actually located much further south, in Florida. Television and movie characters depicted as being “typically Appalachian” sometimes are not even from here (i.e., the quintessential Appalachian bumpkins, the Beverly Hillbillies, were from the Ozarks in Missouri!). Many people can’t even pronounce the word “Appalachia.” While those in the northernmost areas may use the “App-ah-lay-chee-uh” pronunciation or some other “outsider” version of the word, the pronunciation favored by those who live here, particularly in the southern Appalachian mountains, is “App-uhh-latch-uh.” In other words, we’ll throw an “apple-at-cha” if you use the pronunciation favored by those who generally look down upon and exploit the people of Appalachia.

I often find myself explaining where Appalachia actually is when I visit other parts, something I see as a joy, not a burden. So many people think they know about the mountains based on what they saw in a movie or heard about in an article when those filmmakers or writers neither knew nor loved this region. For me, it is a privilege to take people by the hand and lead them to the people, the mountains, the history, and the culture that I love. I hope they will see some of what I think makes Appalachia unique and important.

As an Appalachian person in both location and culture, my perspective is inextricably bound to these mountains. It is a perspective that is both traditional and innovative, both independent and connected, both determined and adaptable, both practical and creative, both fatalistic and faith-driven. Just like the weather, which can go from cold and snowing to hot and sunny in the course of a day, Appalachia and its people are often paradoxical.

So perhaps it is not so strange that I use technology to discuss traditional beliefs and practices (and to criticize some of the issues technology creates). Perhaps it is not so strange that I should be a student of the Inklings, all of whom were men and none of whom were from Appalachia. Paradoxes are one of the beautiful motifs running through my own work and that of these remarkable authors, men whose work frequently invites us to see the beauty and joy that are so powerful they bring us to tears. As an Appalachian, I understand paradoxes, and perhaps, that is one reason why I so dearly love and seek to better understand the Inklings.

From the USGS.